Newborn babies are weighed and measured regularly to check they are growing well and thriving. Weight is the variable most often used to measure growth or faltering growth in the UK. When breastfeeding is going well, a baby’s weight will roughly follow the shape of one of the pre-drawn curves (or centiles) on the weight-for-age charts in a baby’s child health record (called “the red book” in the UK). But what if a breastfed baby’s growth curve is much flatter or steeper than the lines on the chart?

This article

This article looks at what to expect in terms of normal growth for healthy, term babies; how to interpret your baby’s weight chart; when to be concerned about your baby’s weight, and when to take action. This is a companion article to Baby Not Gaining Weight and Is My Baby Getting Enough Milk?

Normal growth in the breastfed baby

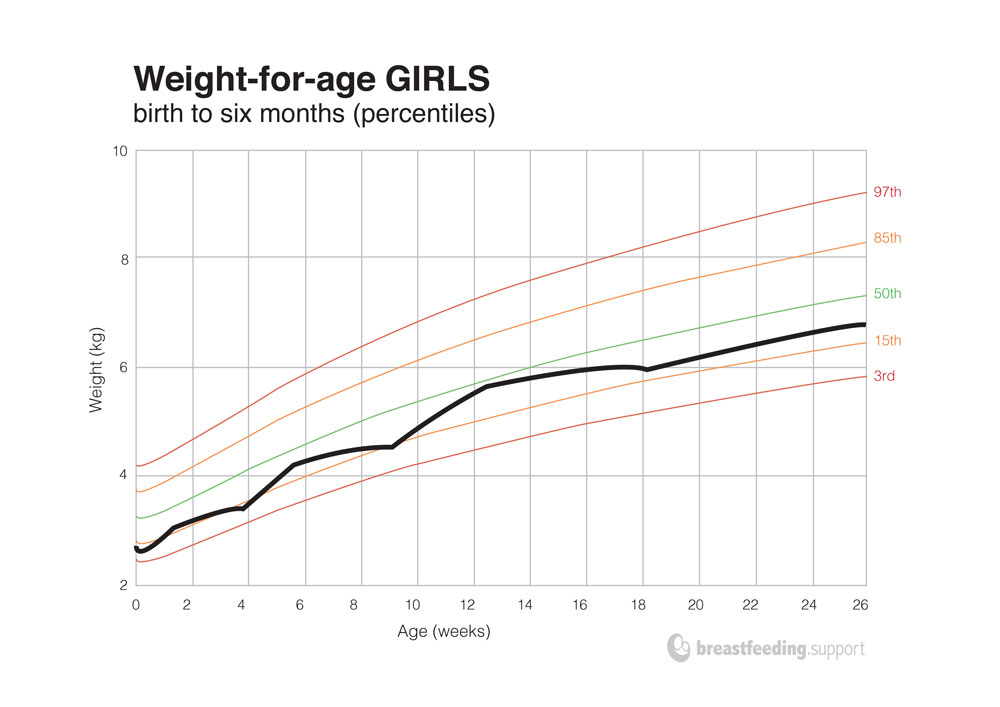

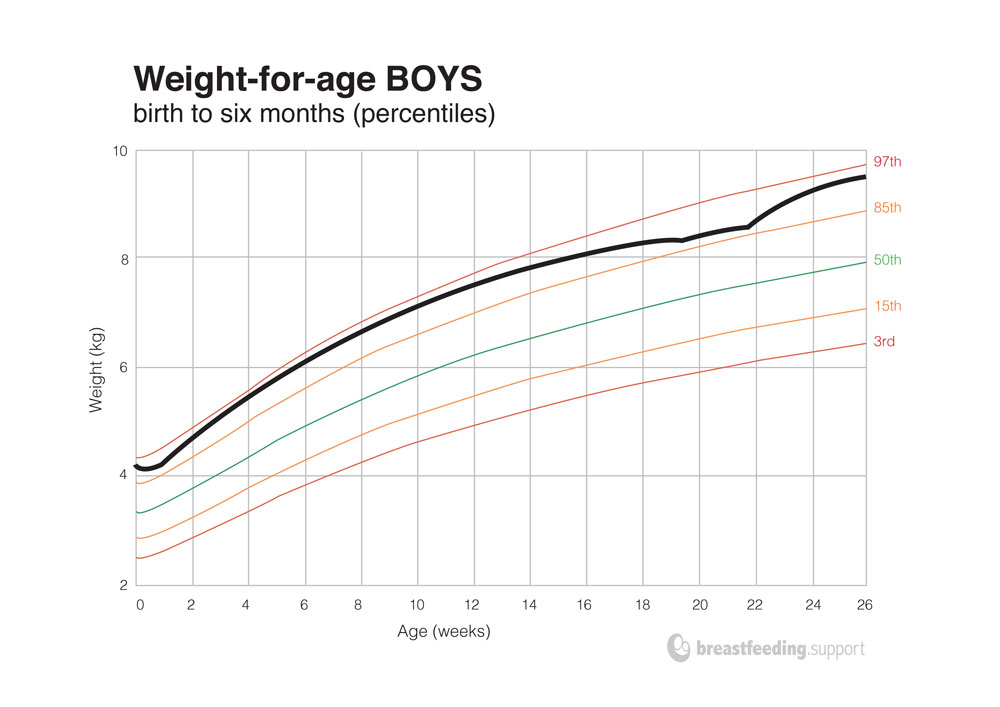

In 2006 the World Health Organisation (WHO) published new growth standards that reflected the normal range of growth in healthy term breastfed babies across the world from non-smoking mothers. These are the charts that have been used in England since 2009 and replace charts that were previously based on growth in formula-fed babies. There are separate coloured charts for boys and girls because they grow at slightly different rates. Follow the links to see the WHO weight-for-age charts for 0-6 months (percentiles) for boys (blue) and girls (pink).

Normal loss and gain

- Weight loss in the first two to four days. Breastfed babies typically lose a little weight in the first two to four days of life before the mother’s milk “comes in” (increases in volume after birth). Losing 7-8% body weight by the third day after birth is common among healthy, full-term, breastfed newborns.123

- After the first few days. After the initial few days, weight gains of 30‑40g per day (or 7‑10 ounces per week) can be expected in the first three months of life based on the World Health Organization (WHO) weight-for-age charts. Weight gain slows down somewhat between 3‑6 months with an average gain of around 20g per day in that period.

Regaining birth weight

It is commonly accepted that babies will be back to birthweight by two weeks of age 45. Macdonald et al 6 found that breastfed babies regained their birthweight by an average of 8.3 days of life.

Unexpected weight loss

A baby may have a higher than expected weight loss in the first few days if a mother had IV (intravenous) fluids during labour 78910 or if breastfeeding is not going well. Monitoring your baby’s poop during the early days can help with identifying milk intake; if milk is going in to your baby, lots of poop will usually be coming out (and be yellow by day five).

Later

Babies generally double their weight in the first four months and will have tripled their birth weight by the end of the first year (WHO growth standards, 2006).

What are centiles?

Centiles divide the range of normal weights into 100 parts and are a useful measure of percentage in statistics. All healthy children will grow somewhere between the 1st and 100th centiles. The lines marked as 3rd, 15th, 50th, 85th and 97th on the WHO charts are known as percentiles or centile lines. For example:

- If your baby is growing along the 3rd centile they are one of the smallest babies for their age. For every 100 babies only three weigh less than him or her (3%) and 97 weigh more (or 97%).

- The 50th centile represents an average weight of all babies. Half of all healthy babies will be below this line, the other half will be above and one is not better than the other.

- If your baby is growing along the 97th centile they are one of the largest babies for their age. For every 100 babies, 97 babies weigh less than him or her and only three (or 3%) weigh more.

UK growth charts

In the United Kingdom, midwives and health visitors will record a baby’s weight in his or her personal child health record (red book). The growth chart in the red book is based on the WHO Child Growth Standards but shows a greater range of centile lines. The red book charts have 0.4 centile, 2nd, 9th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 91st, 98th and 99.6th centile lines marked—see the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) website. The red book charts are quite a small chart size and can be difficult to plot accurately. If you’re not sure whether the chart in your baby’s record is for breastfed babies or has been plotted accurately you can plot your baby’s weight yourself by downloading the appropriate WHO chart (boys 0‑6 months and girls 0‑6 months) or UK-WHO Chart.

Following centiles, normal growth

Growth patterns vary between babies and growth rarely follows a textbook curve. However, weight gain usually tracks within the space or equivalent space between two adjacent centile lines on the chart (the centile space).11 There will be periods of slower and faster growth. Despite fluctuations, the general direction of growth will follow the pre-drawn curves.

Above charts adapted from the WHO child growth standards chart, source: who.int/childgrowth/standards/weight_for_age/en/ accessed 20/09/2016

Crossing centiles and centile spaces

Crossing a number of centile lines or centile spaces downwards can be of concern because if a baby is not growing normally, his health could be at risk. Based on the UK charts* found on the RCPCH website, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have the following guidelines for thresholds of concern for faltering growth:

Consider using the following as thresholds for concern about faltering growth in infants and children (a centile space being the space between adjacent centile lines on the UK WHO growth charts):

- a fall across 1 or more weight centile spaces, if birthweight was below the 9th centile

- a fall across 2 or more weight centile spaces, if birthweight was between the 9th and 91st centiles

- a fall across 3 or more weight centile spaces, if birthweight was above the 91st centile

- when current weight is below the 2nd centile for age, whatever the birthweight.

*Note that these guidelines are based on UK charts which have a greater number of centile lines compared to the WHO versions.

Reasons for a fall across centile lines might include:

- Baby not getting enough milk (the most common reason).

- A medical problem or genetic syndrome.

- Normal adjustment. Some babies who cross centiles may simply be adjusting from the nutritional conditions in the uterus to their genetic potential for growth.12 Perhaps their parents are both small and petite.

Faltering growth

If your baby’s growth continues to falter, their weight could eventually drop below the chart altogether and your baby’s health could be compromised. Stay in close contact with your health professionals and breastfeeding expert if your baby’s weight is crossing centiles and see the examples and ideas for action below.

So how is a doctor supposed to know which of the children who fall under the three percent curve are sick and which are healthy? Well that’s why the doctor went to medical school.

Monitoring growth

Weight is generally used to measure growth but a baby’s length, and head or upper arm circumference may be measured too. Other signs that your baby is getting plenty of breast milk include your baby having plenty of wet and dirty nappies (diapers), your baby’s urine being pale coloured, and being contented between feeds—see Is My Baby Getting Enough Milk? for a summary.

How often to weigh your baby

Historically babies were weighed weekly in the UK. More recently, official advice in the UK has swayed towards weighing once a month between the ages of two weeks and six months, and less often after this time.1314 While this frequency of weighing might be reasonable when breastfeeding is going well and a mother has good breastfeeding support, breastfeeding is not always established yet by two weeks after birth. If breastfeeding is not going well, leaving a newborn baby with poor or borderline weight gain for four weeks is too long both for baby’s health and for his mother’s potentially dwindling breast milk supply.

Weigh weekly until breastfeeding is established

Until breastfeeding is well established, and you are reassured that your baby is easily gaining between 30g and 40g per day, weighing regularly will pick up any problems with weight gain early—so that help can be given to increase baby’s intake of breast milk. The sooner problems are addressed the better for your baby and your milk supply.

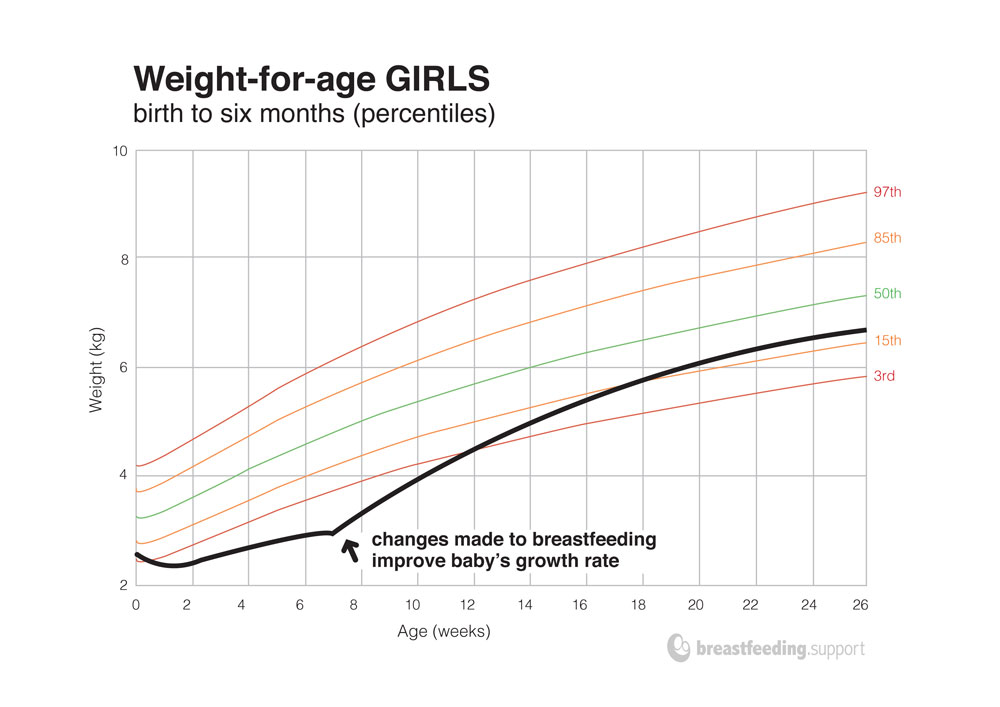

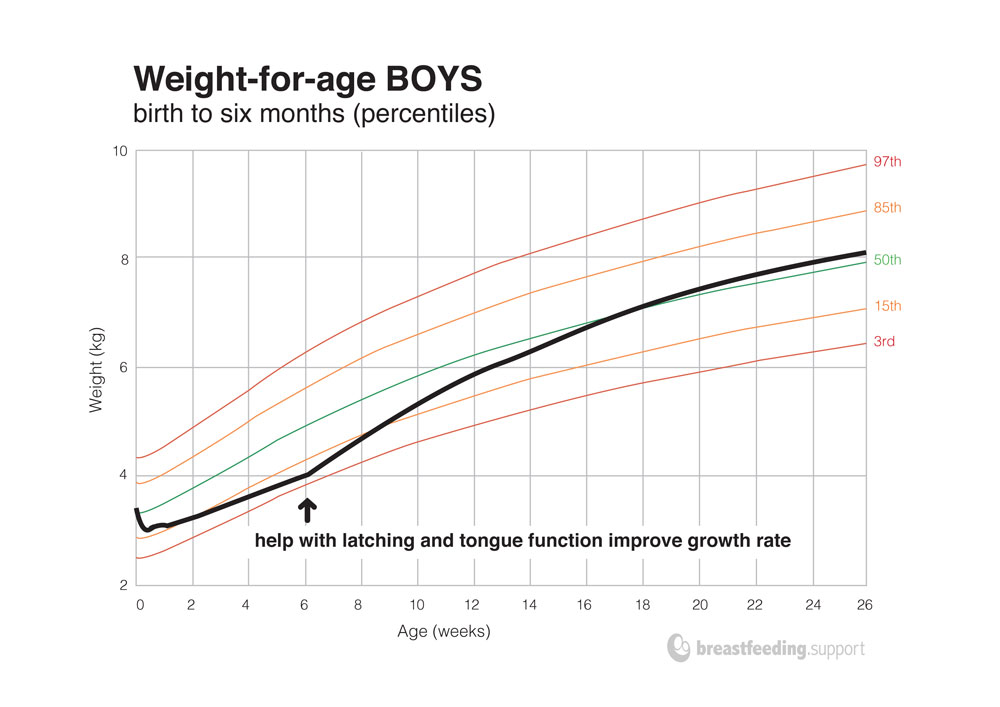

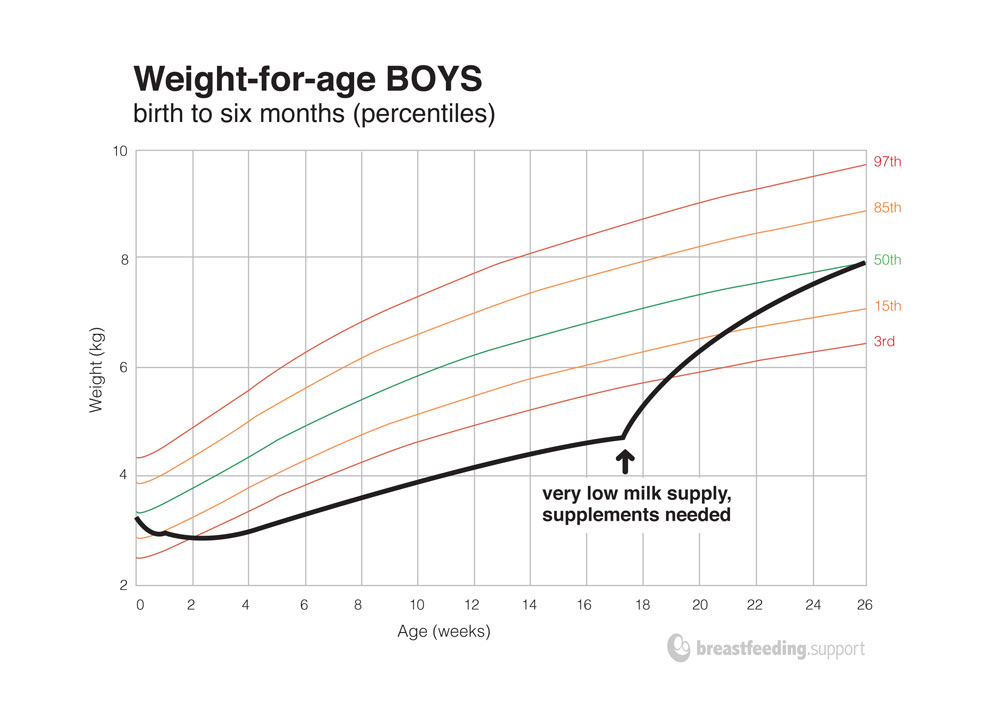

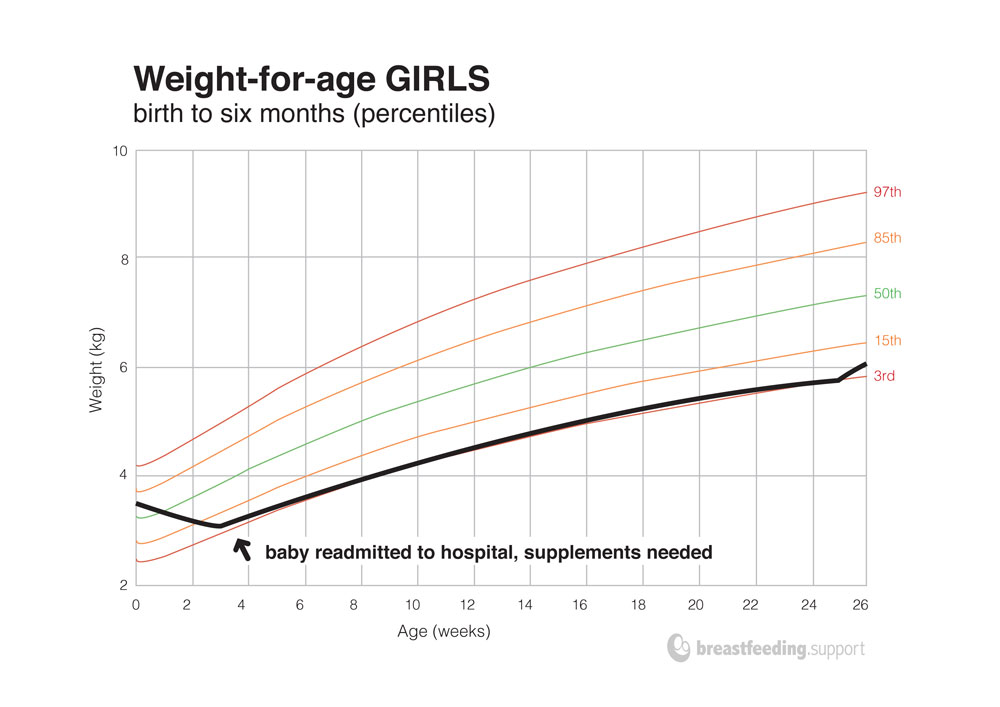

Examples of growth faltering

The following scenarios are hypothetical and simplified, although they mirror real cases of poor growth associated with breastfeeding issues. Always consult with your health professionals if you have any concerns about your baby’s weight. Charts adapted from the WHO child growth standards: accessed 20/09/2016.

Growth faltering due to poor breastfeeding management

In this example baby A’s weight faltered for nearly seven weeks. Her mother had been told to feed from one breast per feed every three to four hours (“to get to the hindmilk”) and her milk supply gradually dropped as a result. Simple changes such as increasing the frequency of feeds to every two hours or more, using both breasts per feed, using breast compressions and pumping will all help to increase milk supply. If mother’s milk supply responds quickly, formula supplements (or donor milk) will not be needed and in this example, baby A’s weight gain steadily improves once she gets more breast milk.

Growth faltering due to difficulty latching or poor tongue function

In our second scenario baby B’s weight dropped across two centile lines (50th and 15th) during his first six weeks of life despite frequent feeding. On the UK-WHO charts this little baby would have crossed the 50th, 25th and 9th centile lines. Baby B might be very fussy and restless when feeding—often coming off the breast—or might fall asleep after a very short feed. Help from a breastfeeding specialist might identify poor positioning, latch, a tight frenulum (membrane under the tongue), high muscle tone, or find a combination of issues for adjustment. Once breastfeeding issues are addressed at six weeks, baby B gains more weight.

Growth faltering and supplements needed

Baby C’s weight had been faltering for four months. Although they might still be bright and alert, baby C would be very small and health care workers would be concerned. Baby C might breastfeed constantly but without “driving” his mother’s milk supply—which would be very low after four months of poor feeding. Donor milk or supplemental formula would be needed here to provide immediate calories while work began on building mother’s milk supply. A very underweight baby might initially bring back some of the top ups as his stomach would be used to small volumes. Within a day or so these babies often respond with a voracious appetite and might gain as much as 100g-120g per day for the first few days, and continue with good catch-up gain—until baby reaches the weight they should have been. See Supplementing an Underweight Baby for more information about supplementing while protecting breastfeeding.

Weight loss, hospital admission

Baby D continued to lose weight for nearly three weeks before being admitted to hospital for tests and supplemental feeds. In those first weeks, health care workers may have believed breastfeeding could pick up on its own. However, intervening with good breastfeeding management at the first sign of continued weight loss at three or four days of age could have avoided this high weight loss and potentially irreversible damage to this mother’s milk supply. There can be many reasons for low milk supply or seemingly no breast milk after delivery, while these are being addressed, a baby needs to be fed with donor milk or formula.

When to take action

Take action early

As soon as weight gain falters consistently, a health check from your baby’s doctor to rule out medical issues and a breastfeeding assessment from a specialist to get breastfeeding back on track, can prevent a cycle of further weight loss, sleepy baby, and low milk supply ending in formula supplements. There are lots of ways to increase a milk supply so that baby can gain 30–40g per day, but sometimes supplements will still be needed. If your health professional or breastfeeding helper doesn’t seem sure how to review breastfeeding, contact an IBCLC lactation consultant for a full assessment and see Baby Not Gaining Weight.

Don’t “wait and see”

Advice from health professionals, friends or family to wait and see what baby’s weight is like in a week/fortnight/month, under the assumption that it can take a while to get breastfeeding established, is time wasted when you could be identifying fixable reasons for low milk intake—and making sure your baby gets the calories he needs. Equally, advice to start topping your baby up with formula after each feed without looking at breastfeeding management, misses the opportunity to problem solve to get back to exclusive breastfeeding where possible.

Breastfed baby gaining too much weight?

Babies above the 99.6th centile for height are almost always healthy 15. If a child’s weight is above 99.6th centile or if their weight and height centiles are very different, the advice from Department of Health (UK) is to calculate their body mass index (BMI). Over the age of two years, the BMI is the simplest way to measure whether a child is overweight or underweight. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States do not recommend BMI-for-age growth charts for children younger than two years of age 16. To plot weight against length for children under two years refer to the WHO Child Growth Standards for length/height.

Breastfeeding is thought protective against obesity in later life,1718 however, certain health issues can be a cause of unusually high weight gain, so always stay in close contact with your health professional if you have any concerns about your baby’s weight.

Summary

Although breastfeeding is the normal and natural way to feed a baby, situations can arise where babies may not thrive. A growth curve that starts dropping through several pre-drawn centiles on the WHO charts can indicate growth faltering, but there’s no need to wait until this happens before taking action. Taking action as soon as there are growth concerns—by seeing your health professional and a breastfeeding specialist— can prevent compromising both your baby’s health and your milk supply later. The sooner a low milk supply is addressed the easier it is to fix it. If donor breast milk or formula supplements are needed, this doesn’t have to mean the end of breastfeeding—it is very important that your baby is getting the food they need. Contact your IBCLC lactation consultant for a tailor made care plan to get breastfeeding back on track and see Baby Not Gaining Weight for more information.

If you have any worries about your baby’s weight gain or growth contact your health care professional for help. This article is not intended to replace medical advice.